|

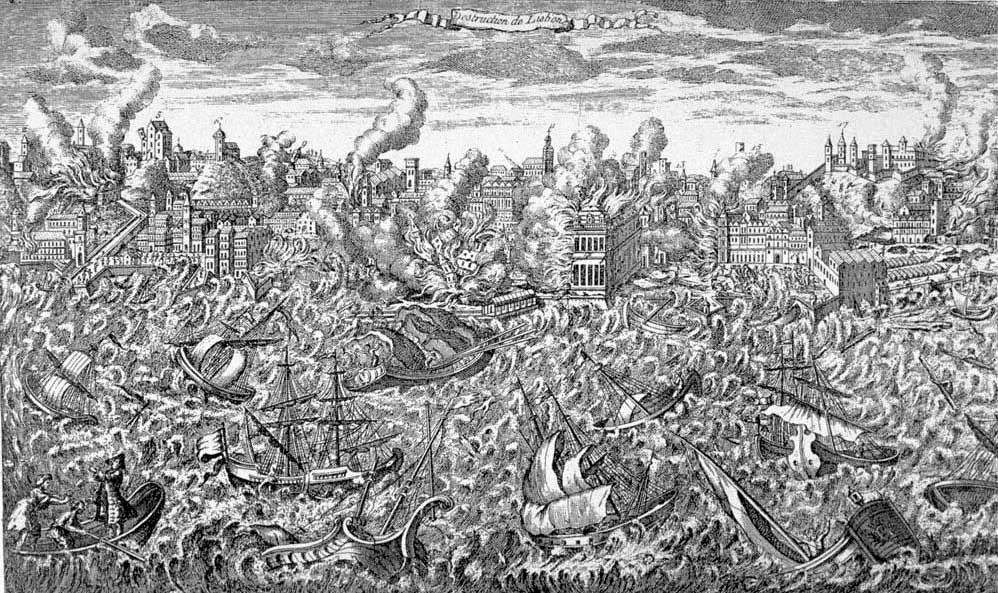

| A study of the tsunami and earthquake at Lisbon 1755 |

Apart from the shocking loss of life, and devastation, the earthquake also had a number of unforeseen consequences. These included such diverse developments as the virtual birth of seismology as the science of predicting earthquakes, as well as a stay of Portugal's efforts to be seen as as a great colonial and naval power. Perhaps the most provocative consequence of such an obviously world-shattering event was that it initiated a dialogue between the great philosophers of the period, who attempted to hijack any explanation of the earthquake away from the teachings of the Roman Catholic church and toward a discussion of the new Enlightenment way of thinking. In the later twentieth century, the Lisbon earthquake has been compared to the Jewish Holocaust, in its power to transform the culture and philosophy of Europe because of the destruction it caused, and the terrible human suffering that was its consequence. After all, this was still a period in European history that condoned such things as the burning of witches, bleeding people with leeches when they were sick, as well as the refutation of anything that disagreed with the Aristotelian view that the sun revolved around the earth, two hundred years after Galileo had made his discoveries to the contrary.

What followed was a remarkable discourse between members of the European intelligensia which openly mocked the teachings of the church in order to educate the common people on the powers of the new concept of reason as a method for them to improve their lot, removing the shackles of superstition from an ignorant landed peasantry, and enabling them to question the subservience they were expected to observe to a higher deity. The earthquake had ironically struck on the Catholic holiday of All Saints Day. Virtually every important church in the city had been destroyed and theologians rushed to explain the catastrophe away as the divine judgment of God, much to the chagrin of the survivors who had lost their loved ones, whilst the King of Portugal and his family had been spared after taking their leave of the city for a holiday the night before the quake occurred.

The great enlightenment French philosopher Voltaire took the opportunity to attack the prevailing philosophical thought of the epoch which was described by Leibniz as 'all's for the best in the best of all possible worlds' by writing the poem 'The Disaster of Lisbon' : "Come ye philosophers, who cry, all's well/ and contemplate this ruin of a world." In Candide the Optimist, Voltaire has Candide, the eternal optimist exclaim: "if this is the best of all possible worlds, what are then the others". In 1757 Samuel Johnson gathered to the fray and defended Voltaire's more realistic response by disparaging fellow Englishman Alexander Pope's insistence that things would somehow be put to right by stating "Pope thus never saw the miseries which he imagines thus easy to be borne." Optimism, Voltaire declares, "is merely an insult to the miseries of our existence" and only the churchmen whose churches were destroyed are foolish enough to believe that evil does not, at least sometimes, prevail over good. In 1756 Rousseau scolded Voltaire in a letter that complained that taking away religion reduces the human race to a despair far worse that it would suffer without it, but it seems that Voltaire had the ear of the people and perhaps offered them more solace than any of the churchmen ever managed.

|

| A tent city was built. Looters were hung as an example by King Joseph I |

The city of Lisbon, once the most beautiful in all of Europe, was eventually rebuilt, but the earthquake which destroyed it, also destroyed the confidence and equilibrium of a Europe which pictured itself as the most important power in the world. Lands in America were being conquered, trading routes were opening up and the future looked bright for the bourgeoisie, the merchants and the conquistadors. Rumours spread about how the disaster was an omen from God, or a way of punishing the King of Portugal for his wickedness in mistreating the indigenous south American Indians. This is of course only superstition, for as Werner Hamacher has stated, it was the foundational certainty of Descartian philosophy that began to shake after the Lisbon earthquake.

Works consulted: the full text of the Disaster of Lisbon here; relevant Wikipedia article here; Lisbon earthquake here; Historical depictions of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake here; Lisbon pre-1755 Lisbon earthquake here; and link to popular history work best known at the moment here.

No comments:

Post a Comment